Royal obsession

November 25, 2010 § 2 Comments

[L]et the press … be busy in propagating the doctrines of monarchy and aristocracy. … the quiet hereditary succession, the reverence claimed by birth and nobility, and the fascinating influence of stars, and ribands, and garters, cautiously suppressing all the bloody tragedies and unceasing oppressions which form the history of this species of government. No pains should be spared … to convince them that a king, who is always an enemy to the people, and a nobility, who are perhaps still more so, will take better care of the people than the people will take of themselves.

—Philip Freneau, “Rules for Changing a Republic Into a Monarchy,” 1792

We have got living idols, instead of dead ones; and we fancy that they are real, and put faith in them accordingly.

–Henry Hazlitt, “On the Spirit of Monarchy”

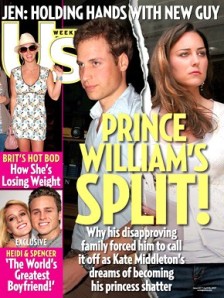

SAYS HERE THAT 26 percent of Americans don’t know we separated from England in 1776. It’s hard to blame them, what with the saturation coverage our media shower upon the frivolous lives of foreign, astronomically wealthy welfare leeches — or, as the media call them, “The Royal Family.”

Assuming for the moment that American viewers actually demand this drek, it might illuminate some realities about our own society: our fascination with glamor and celebrity and wealth and power — however dubiously acquired — and the fatal compulsion among the bedazzled masses to bask in the glory of pampered elites which, they suppose, somehow reflects back upon them.

The founders of the States of America, with few exceptions, saw any move toward royalism as a step backwards on the path of human progress. They would have been dumbfounded at the overwhelming attention future Americans would shower on the degenerate offspring of ancient usurpers of the sort the founders spilled their blood to fight.

There has always been an Anglo/Europhile thread at certain levels of American society, a belief that all things European are automatically superior. There’s also the lamentable reality that the common masses seem almost biologically programmed (and/or bred) to be awed by peacock-like costumes, shiny baubles, rituals and pageants that mystify and mesmerize as reliably as tucking a bird’s head under his wing puts him to sleep. And, weirdly, many people seem to have a subconscious need to be dominated.

Robert Coover, postmodernist children’s book writer, said in an interview:

We are … an allegedly democratic society that has thrown off royalty and the naïve awe of bloodlines, yet we flock to see something as blatantly royalist as The Lion King and grovel before political and commercial dynasties, as through somehow their seed might be magical . . .

The popular lore — from the old European fairy tales, down to the Disney versions — presents the glamor and mystique of royalty and feudalism without all the blood, gore and greed and depravity; it’s all wrapped in a gauzy haze of medievalist romanticism of the sort that only a modern people could afford to entertain. We ignore the grubby reality that these types typically came by their power like any group of gang lords: they just killed more of the other guys.

It happens that as all the “Royal Family” news broke last week, I was reading The Cult of the Presidency by Gene Healy (you can read or download it here), which ought to be required reading in every high school American history class. This book tells how elites have transformed the once-humble chief magistracy — intended merely to enforce the will of the People’s representatives — into a near-“unitary executive,” our very own elective monarch, who now presumes to boss the Congress around and “set the agenda” for the nation.

It’s the coteries of sycophants around the presidents, as much as the presidents themselves, who drive this trend. Among the framers, the precursor to Rumsfeld and Cheney was Washington’s treasury secretary, Alexander Hamilton, father of big government, American imperialism, and the national debt, as well as the notion of the Constitution as magical document containing limitless, invisible “implied powers” for the federal government. (A notion diametrically opposite the plain words and spirit of the document itself, which recognizes virtually unlimited rights for individuals but only a few, strictly limited powers for the government.) No sooner had we defeated King George’s army than Hamilton was advocating an American monarchy — or as he called it, a “governor” for life.

Hamilton got his national debt and his central bank, for a while at least. His vision for the presidency, however, never was realized during his lifetime. For the next century, except for notable deviations by Lincoln during the Civil War, the presidency remained humble and unassuming. Throughout the 19th century presidents didn’t dare tell Congress what it ought to do, and refrained from pompous State of the Union speeches, delivering their reports instead by letter.

But the seeds Hamilton had sown awoke from dormancy and sprang to life under William McKinley, Theodore Roosevelt and Woodrow Wilson, watered by a brew of intense economic inequity and social upheaval. Weaving together good Christian ideals, quasi-populist rhetoric, Prussian-Hegelian state worship and scientific racism, a group of elite social engineers, including Wilson, surreptitiously grafted these ideas into American society via state schooling and under the beneficent-sounding banner of “progressivism.”

In the same circles, influential men seriously argued for American reunification with Britain, so that the “superior English-speaking and Teutonic peoples” could fulfill their destiny of world rulership. The reunification effort failed, but only in the literal sense. As their elites and their money intermingled — as American society aped the pretensions of, and married into, British society — the spirit of the Empire at some point transplanted itself to the States.

America, which at the close of the 18th century had seemed mankind’s great hope for liberty and equality, had by the end of the 19th become a plutocrat’s playground. Downtrodden masses and their Populist and Progressive champions demanded relief from economic oppression and political corruption. Rather than heed the words of genuine liberal reformers such as Henry George and founding fathers like Thomas Jefferson — and even the prescient anti-Federalists — the Progressives listened more to Marx. They assayed to fight the business and financial trusts by erecting a political power trust. Under a schizophrenic platform that touted “power to the people” yet centralized power in Washington, the nation careened down the road to serfdom.

Under the baneful influence of the Cult, the president became a national Father, a near-god, literally preceded everywhere he goes by fanfares. The presidents and the elite leadership and intellectual coteries around them exploited — and fomented — crises such as wars, depressions, and civil unrest, always to massively centralize power in the federal government in Washington and especially the executive. The heights of the Cold War were the depths of American captivity to the imperial presidency.

Vietnam, Watergate, and a host of sordid revelations of official corruption and crimes slightly curtailed the nation’s childlike reverence for the imperial presidency. But it regained renewed strength in the wake of 9/11. The American left deplored the arrogant crowings of imperialism when they came from a Bush, but are delighted when their preferred choice of emperor, Obama, wields and indeed expands the same powers in pursuit of the same policies. We don’t have the titles and royal regalia, but we might as well have a king.

Which brings us back to why the media want us worshiping royalty again. We already mentioned the seemingly natural allure of this to many people.  There’s another likely and more direct reason for the love affair with elitism: intentional programming by the elites. Some folks somewhere in key positions realize that propagandizing for modern monarchy, making it hip and giving it youth and sex appeal, transfers easily to our own homegrown monarchy and modern aristocracy of artificial fame, purloined wealth, and purchased power. More than anything else, that explains the engineered, endless assault of publicity of every royal sneeze or butt scratch from across the pond.

There’s another likely and more direct reason for the love affair with elitism: intentional programming by the elites. Some folks somewhere in key positions realize that propagandizing for modern monarchy, making it hip and giving it youth and sex appeal, transfers easily to our own homegrown monarchy and modern aristocracy of artificial fame, purloined wealth, and purchased power. More than anything else, that explains the engineered, endless assault of publicity of every royal sneeze or butt scratch from across the pond.

We have a chance to take America back from both intermarried families of aristocratic privilege — from both Big Money and Big Government. The Cult of the Presidency makes clear the connected nature of the two. (And incidentally, you monotheists out there, it will lead you to reflect on the meaning of idolatry.)

Go get it, it’s free.

[…] See related post Royal Obsession. Rate this:Like this:LikeBe the first to like […]

[…] I used to think the LaRouchies were nutters for saying the British royals run everything, but one has to wonder why CNN is now BBCNN and we are constantly bombarded by “Royal Family” propaganda. […]